Communism's "Fall"

and the Rise of

the "Cool" War

Part I: The "Fall"

...and just like that, it was gone! It all started in 1989, with the country of Czechoslovakia.

On November 17, 1989, a student-led movement known as the "Velvet Revolution" took to the streets in final disgust with communism. It was called the "Velvet Revolution" because it was "soft", and without violence and blood.

This singular movement, starting in the one country that actually adopted communism first after World War II, would lead to similar revolutions elsewhere, and the eventual downfall of the Soviet Union itself...

Part II: The "Present"

And now we come to the modern era. Current Russian President Vladimir Putin’s first

term in office began in the year 2000 and ran until 2008. During this time, the Kremlin (the

Russian “equivalent” of the White House) remained publicly committed to “liberal democracy”. But, during these years, Russian society would witness the

creation of the state-sponsored youth

organization the Nashi, the

imposition of controls on private

businesses and volunteer sectors, draconian

(definition: harsh and extreme) measures against opposition demonstrations,

and the exclusion of the political opposition from competition for public

office. All of this took place during these years of optimism and achievement.

But why? Why would a government promise democracy yet disprove and disavow this agenda time, and time again? In a word, "velvet"... Vladimir Putin and other post-Soviet leaders have remained wary of the appearance of "velvet" ferment in Russia itself…

But why? Why would a government promise democracy yet disprove and disavow this agenda time, and time again? In a word, "velvet"... Vladimir Putin and other post-Soviet leaders have remained wary of the appearance of "velvet" ferment in Russia itself…

Spotlight On: The "Rose" Revolution

The anxiety about “velvet revolutions” among Russia’s political elite dates to the “Rose Revolution” in Georgia, the first of the new wave of democratic revolutions in the post-Soviet space. You can see it on the map above, in the bottom right, right below Russia's borders...

In November 2003, and at the height of mass protests in the capitol city of Tbilisi, Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili boasted that “today we are witnessing velvet, bloodless, democratic and nation-wide revolution which aims at the bloodless removal of [old Soviet rule]”. It was not a term that the Kremlin was prepared to accept.

Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov told Polish journalists that “the classification ‘velvet revolution’ is unacceptable…because there was no velvet there”.

In short, Russia feared a bloody rebellion...

Spotlight On: The "Orange" Revolution

What transformed prospect of a “velvet revolution” in Georgia from a diplomatic challenge into a catalyst for fundamental change within Russia was the upheaval in Kiev, the capitol city in the Ukraine in late 2004.

Unlike other disturbances in the region, the fall of the Soviet-esque regime in Ukraine represented a political earthquake. The rapid succession of Ukraine’s “Orange Revolution” and nationwide mass protests in Russia itself in early 2005 served to galvanize opposition forces and shake the Putin regime. “This is excellent,” said Yuliya Tymoshenko, who would serve as Ukraine’s interim president in the early part of 2014.

“As soon as the Ukrainians finish our ‘Orange Revolution’, we will give our ‘Orange’ attitude to Russia. Something needs to be done there also.” Georgii Satarov, one of the “Orange” organizers, placed his own spin on the events, declaring that ‘the [Putin] regime is afraid neither of our shouts nor our criticism: it is afraid of the Ukrainian scenario, when we all go out on the streets.”

President Putin made no secret of both his anger and annoyance at the progress of “velvet revolution” at his end-of-year press conference on 23 December 2004. Responding to a question about foreign meddling in former Soviet republics, he uttered one of his most famous lines: “What is most dangerous, you know, is the creation of a system of permanent revolution, whether that be ‘rose’ or some yet-to-be-invented ‘blue’”. His comments must be treated with Russian cultural context, as, by emphasizing the colors of “rose” and “blue”, he played on the Russian slang meanings of ‘rose’ as lesbian and ‘blue’ as gay male. And in utilizing the phrase of a “permanent revolution”, he attempted to shed light on the frivolity (definition: lack of seriousness) and useless endeavors of constant change...

“As soon as the Ukrainians finish our ‘Orange Revolution’, we will give our ‘Orange’ attitude to Russia. Something needs to be done there also.” Georgii Satarov, one of the “Orange” organizers, placed his own spin on the events, declaring that ‘the [Putin] regime is afraid neither of our shouts nor our criticism: it is afraid of the Ukrainian scenario, when we all go out on the streets.”

President Putin made no secret of both his anger and annoyance at the progress of “velvet revolution” at his end-of-year press conference on 23 December 2004. Responding to a question about foreign meddling in former Soviet republics, he uttered one of his most famous lines: “What is most dangerous, you know, is the creation of a system of permanent revolution, whether that be ‘rose’ or some yet-to-be-invented ‘blue’”. His comments must be treated with Russian cultural context, as, by emphasizing the colors of “rose” and “blue”, he played on the Russian slang meanings of ‘rose’ as lesbian and ‘blue’ as gay male. And in utilizing the phrase of a “permanent revolution”, he attempted to shed light on the frivolity (definition: lack of seriousness) and useless endeavors of constant change...

"Punched On the Snout"

The mastermind of the Putin regime’s response to “velvet revolutions” was Gleb Pavlovskii, the director of the Foundation for Effective Politics. Pavlovskii attributed the failure of recent efforts to the fact that the revolution was not “punched on the snout”. “Punching the snout” of Russia’s “velvet revolutionaries” became Pavlovskii’s vocation: “It was no longer enough to manipulate elections with phony parties and press coverage,” he said. “The possibility of violence cannot be ruled out”

The Russian youth group called the Nashi were the key to this: they embraced the Soviet past, styling their activists ‘commissars’, launched a website on the “Soviet” domain (www.nashi.su) as opposed to the “Russian” domain extension of “.ru”, and exploited the memory of the Great Patriotic War as a rallying point, a term originally used by Joseph Stalin to refer to the Second World War.

Additionally, they overtly criticized their “Orangeist” adversaries not only as pawns of foreign powers but as “fascists”. In May 2005, the headquarters of the National Bolshevik Party were ransacked by a gang of Russian youths. In September, the same gang used rubber bullets and baseball bats to disrupt a conference of left-wing groups, which had been convened to discuss the creation of a broad alliance of radical youth.

Additionally, they overtly criticized their “Orangeist” adversaries not only as pawns of foreign powers but as “fascists”. In May 2005, the headquarters of the National Bolshevik Party were ransacked by a gang of Russian youths. In September, the same gang used rubber bullets and baseball bats to disrupt a conference of left-wing groups, which had been convened to discuss the creation of a broad alliance of radical youth.

Spotlight On: Ukraine Today

Though it might not be another "colored revolution", but we're in the midst of some more "velvet ferment". Putin's adviser said that the revolutionaries from 2005 needed to be "punched on the snout", but wonder if the "snout" is "digital"? As an "evolution" of the "colored revolutions", let's examine the "digital revolution" in Ukraine.

We know that Russia formally "annexed" the Crimean region in March 2014, and at the present moment, Russian forces remain fixed on Ukraine's eastern border. For now, there is no war, no revolution, no "expulsion" of Russia out of Ukraine because they don't "own" it! So, what are Ukrainians doing to prevent further "Cold War actions"?

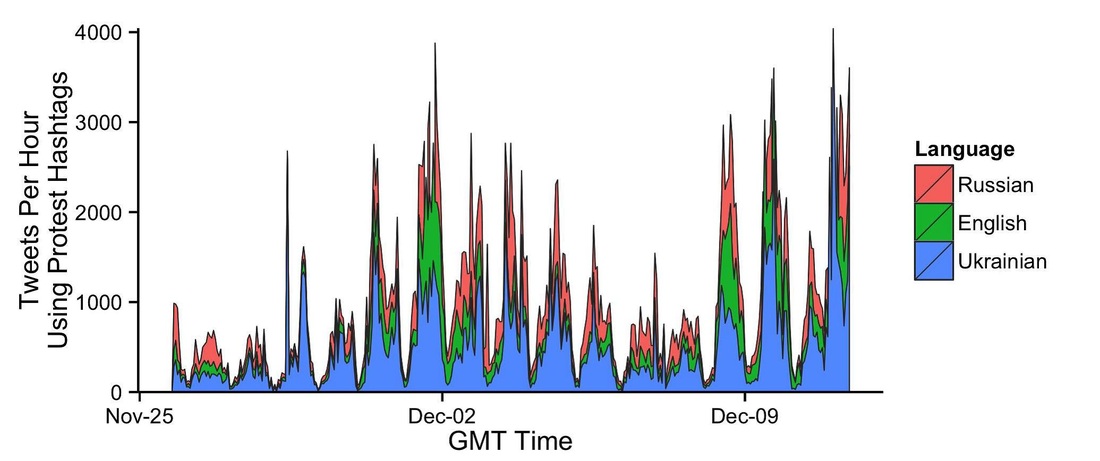

When Cold War tensions started to "heat up" in December 2013, Ukrainians took to the "digital streets" in protest. How? By using the hashtag #EuroMaiden to coordinate protests at the "maiden", a nickname for the capital city's Independence Square. You can see that the tweets were in Russian, Ukrainian, and English!

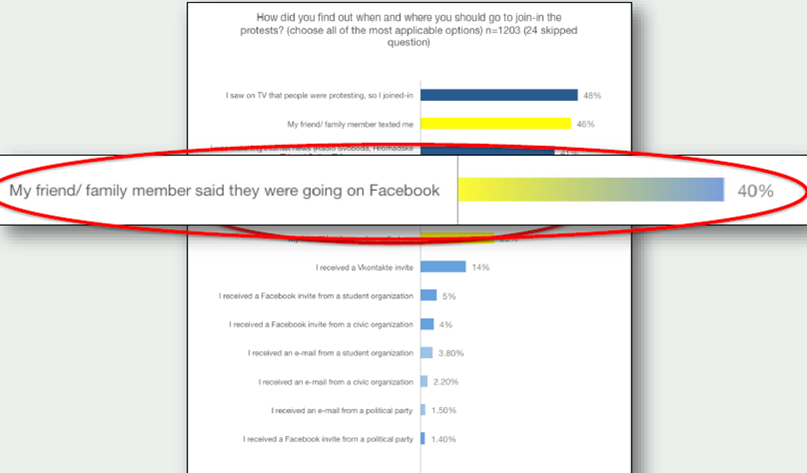

When asked about how they "find out" where and when to join protests, some said, "Television" or "Family", but many said, "My friend / family member said they were going on Facebook".

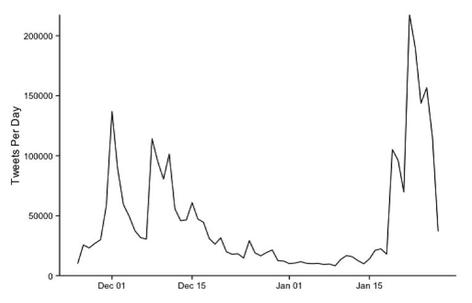

The usage of Twitter and #EuroMaiden blew up in January 2014...

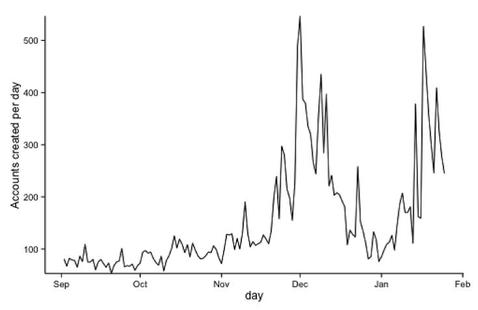

...which prompted a huge rise in Twitter accounts created per day!

The future of Ukraine is still up for grabs. There are many Ukrainians who side with Putin and the former Soviet sphere...

...but many others stand on guard, like current political leader Yulia Tymoshenko (right), awaiting the rise of another Cold War.