"Strong Borders, Strong Governments"

An Assessment of Government Industrial Strength In the 18th and 19th Centuries

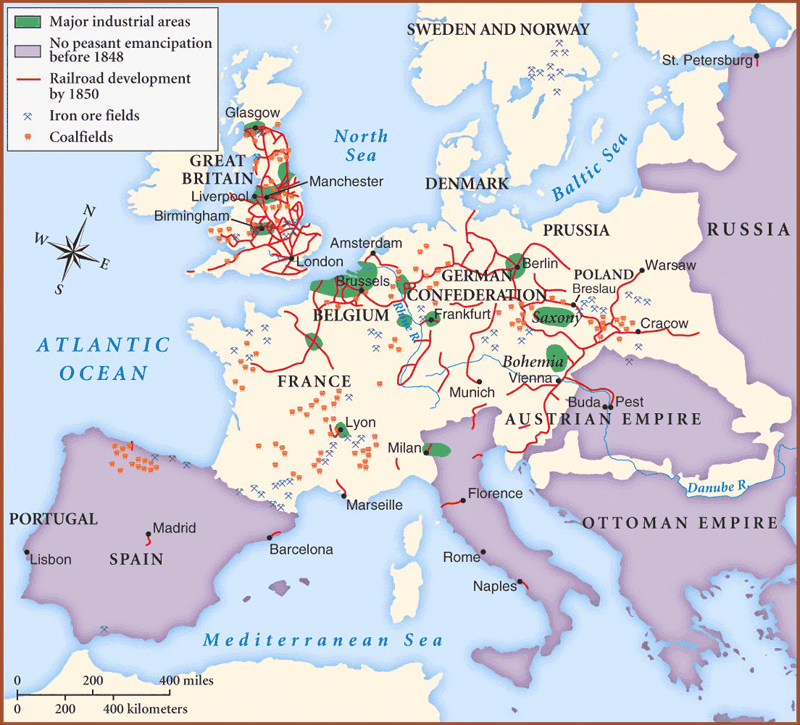

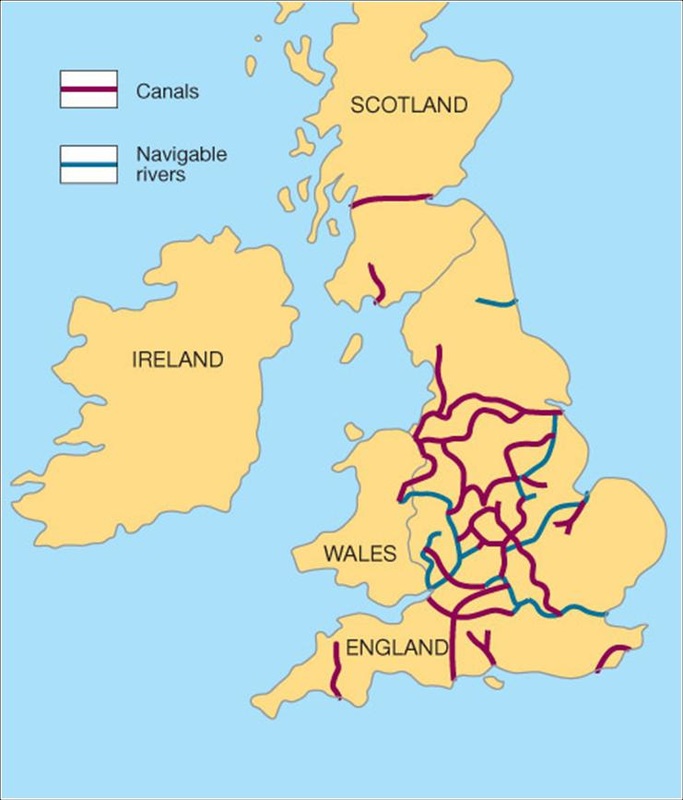

The question is simple: which nations industrialized, which didn’t, and why? Employing a DBQ-like approach, and using a variety of scholarly research, data, and perspectives, arrange your country placards in order, and in your notes, provide the justification for your rankings.

Document 1: Early Industrialization in Europe: Concepts and Problems, by R. A. Butlin (Mar., 1986)

EXCERPT, EDITED AND ABRIDGED:

“Proto-Industrialization”, the first phase of the industrialization process, has been characterized as the organization by merchant capitalists with small farms or holdings, predominantly in areas of agricultural and environmental marginality, and geared to seasonal rhythms of production, and distinctive inheritance patterns. We’ve come to know this as the “putting out” system.

The need to maximize the total labor force (husband and wife and children) of the peasant household provided powerful incentives for parents to have more children...We’ve found that proto-industrialization was most likely to occur where urban and rural needs complemented each other, that is, where poor peasants, especially poor women peasants, met prosperous textile merchants. Craft industries were important in many parts of the French countryside in the 1830s; In fact, few villages in France were without workshop trades. The increase in competition from the mid-nineteenth century, especially with imports from England and Germany, gave rise to an eventual concentration and mechanization of production in major cities.

The case of Germany is a different story. Although initially receptive of industrial change, heavy competition with English imports in the mid-nineteenth century led to the deindustrialization of many of the villages, resulting in heavy emigration through to the end of the nineteenth century as a consequence.

“Proto-Industrialization”, the first phase of the industrialization process, has been characterized as the organization by merchant capitalists with small farms or holdings, predominantly in areas of agricultural and environmental marginality, and geared to seasonal rhythms of production, and distinctive inheritance patterns. We’ve come to know this as the “putting out” system.

The need to maximize the total labor force (husband and wife and children) of the peasant household provided powerful incentives for parents to have more children...We’ve found that proto-industrialization was most likely to occur where urban and rural needs complemented each other, that is, where poor peasants, especially poor women peasants, met prosperous textile merchants. Craft industries were important in many parts of the French countryside in the 1830s; In fact, few villages in France were without workshop trades. The increase in competition from the mid-nineteenth century, especially with imports from England and Germany, gave rise to an eventual concentration and mechanization of production in major cities.

The case of Germany is a different story. Although initially receptive of industrial change, heavy competition with English imports in the mid-nineteenth century led to the deindustrialization of many of the villages, resulting in heavy emigration through to the end of the nineteenth century as a consequence.

Document 2: Why England? Demographic Factors, Structural Change and Physical Capital Accumulation During the Industrial Revolution, by Nico Voigtländer and Hans-Joachim Voth (Dec., 2006).

EXCERPT, EDITED AND ABRIDGED:

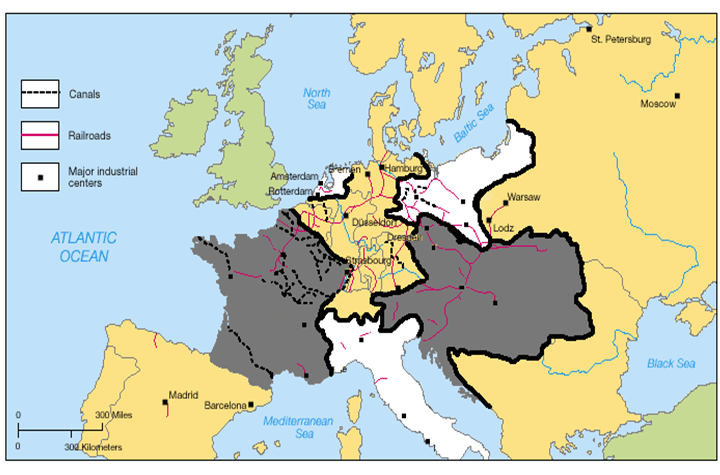

Why England? Economic historians have stressed a long list of factors, ranging from the property rights regime to the land tenure system, which might have favored Britain. [But]...in our studies, we find that England's chances of sustained growth were greater principally because of the following demographic factors:

Why England? Economic historians have stressed a long list of factors, ranging from the property rights regime to the land tenure system, which might have favored Britain. [But]...in our studies, we find that England's chances of sustained growth were greater principally because of the following demographic factors:

- Economics and human capital. Britain had a surplus of "liquid cash" along with an abundance of human capital ready to be utilized in the industrial process.

- Government support. With a government system focused on the redistribution of wealth and power, seen primarily in the “Old Poor Laws” that transferred amounted to 2.5% of British GDP in the form of “relief” to more than 11% of the population, British industry saw its greatest "cheerleader" in its government.

- Food and Nutrition: Conversely to Britain, take France for example: As many as 20% of the population in 18th century France possibly did not receive enough food to work for more than a few hours a day. So how could they possible sustain 14-hour work days in grueling factory conditions? Estimates show that the British consumed some 17% more calories than their French counterparts.

- An Entrepreneurial Spirit: Another school of thought in relation to England’s dominance argues that bigger markets are better able to adopt new technologies and keep them going. New technologies represent “high risk, high return” investment, and because of indivisibilities, only richer and larger countries undertake them. But the “retooling” of existing technology was also paramount: the Watt steam engine was but a variation of the Newcomen design (a British-made steam engine invented a century earlier).

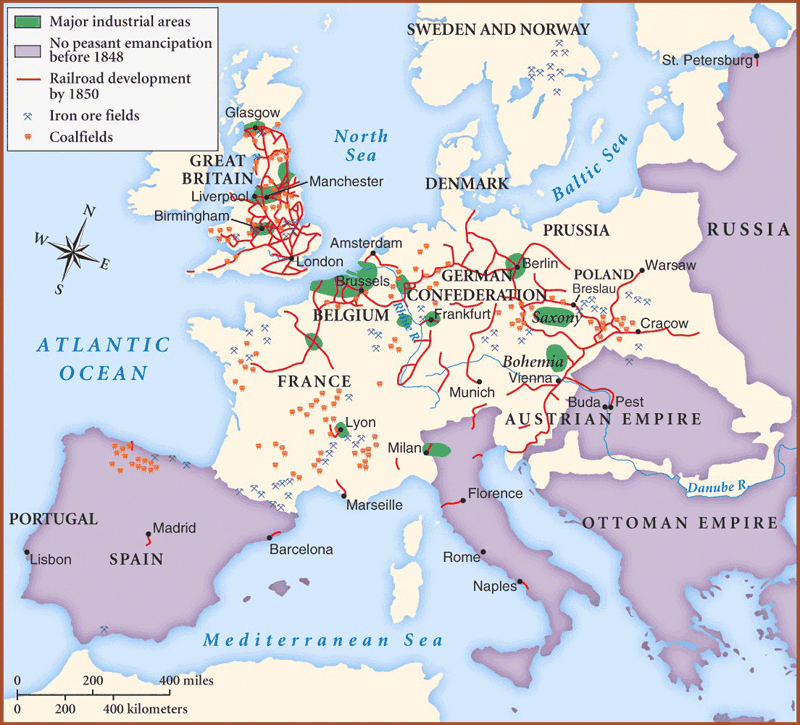

Document 3: The German Zollverein and the European Economic Community, by W. O. Henderson, (September 1981).

EXCERPT, EDITED AND ABRIDGED:

The only organization in the nineteenth century which can be compared with the European Economic Community (the so-called “European Union” and the relaxed trade boundaries of today) is the Zollverein, the customs union which linked nearly all the German states, with Prussia being the biggest, accounting for 54% of the population. In both cases it is reasonable to argue that the states which united enjoyed a greater economic growth than they could have hoped to achieve in isolation. In Prussia for example, just before the establishment of the Zollverein, the revenue from customs duties accounted for little over 40% of total taxation revenue. But, with the addition of a “direct tax” on non-Zollverein member countries, revenue was significant that any other forms of economic taxation was essentially rendered superfluous.

In conclusion, yes, the Zollverein was a customs union, but soon established a fixed relationship between its members. The main currencies became aligned and, as time went on, the members of the Zollverein made agreements on rail and river transport, on postal arrangements, on bills of exchange and much else.

The only organization in the nineteenth century which can be compared with the European Economic Community (the so-called “European Union” and the relaxed trade boundaries of today) is the Zollverein, the customs union which linked nearly all the German states, with Prussia being the biggest, accounting for 54% of the population. In both cases it is reasonable to argue that the states which united enjoyed a greater economic growth than they could have hoped to achieve in isolation. In Prussia for example, just before the establishment of the Zollverein, the revenue from customs duties accounted for little over 40% of total taxation revenue. But, with the addition of a “direct tax” on non-Zollverein member countries, revenue was significant that any other forms of economic taxation was essentially rendered superfluous.

In conclusion, yes, the Zollverein was a customs union, but soon established a fixed relationship between its members. The main currencies became aligned and, as time went on, the members of the Zollverein made agreements on rail and river transport, on postal arrangements, on bills of exchange and much else.