Stasiland:

Life Behind 'The Wall'

"On the night of Sunday, 12 August 1961, the East German army rolled out barbed wire along the streets bordering the eastern sector, and stationed sentries at regular intervals. ..Some made a dash through the wire...Others who lived in apartments overlooking the borderline started to jump from the windows into blankets held out by Westerners on the footpath below...Then the troops made residents brick up their own windows. They started with the lower floors, forcing people to jump from higher and higher windows."

This is an excerpt taken from the book Stasiland, written by Australian author Anna Funder, whose in-depth reporting tells the stories of those who lived "life behind the Wall". Most of those "behind the Wall" lived life in extremes: "extreme" paranoia and "extreme" want. Others lived life in excess: "excessive" power and "excessive" priviledge. She tells the stories of mothers, fathers, sons, government officials, and members of the Stasi: the Nazi-esque police force that kept order in the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR), which translates to the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

As a way of understanding "life behind the Wall", let's walk through Stasiland the book, but more importantly, the State! As if you were on a "field trip", examine the images, pictures, quotes, data, and factual excerpts below and draw a conclusion at the end.

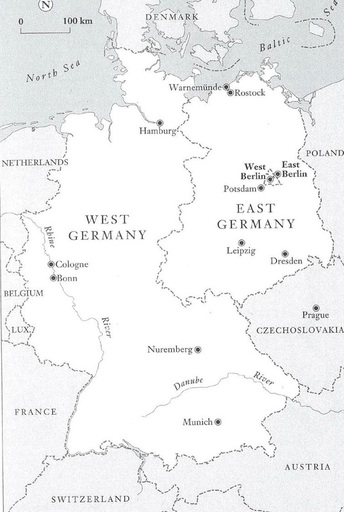

Let's start with the basics: The postwar conferences divided Germany into sectors. Eastern Germany, containing the city of Berlin, was "owned" by the Soviets, and therefore, would operate under the communist system.

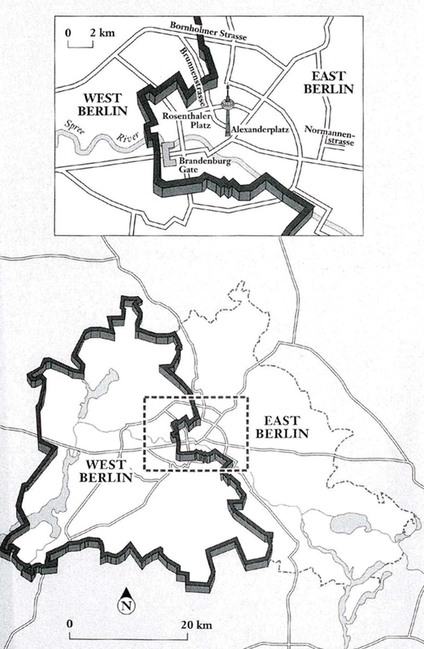

As mentioned above, Berlin, the capital city, was divided into four (4) sectors, even though it was entirely contained inside of the Soviet quadrant. West Berliners may have lived in the French, British, or American sector, and operated under the capitalist, democratic system. East Berliners, those "behind the Wall", lived in the Soviet sector and operated under the communist system.

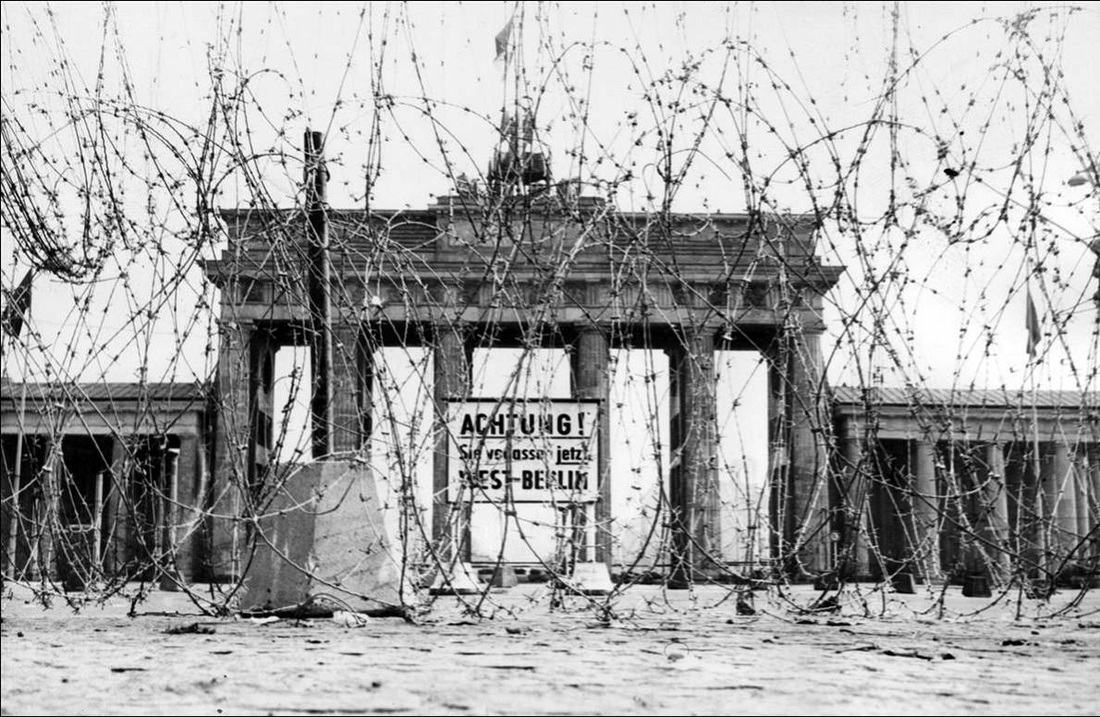

If you examine the "up-close" Wall-Map above, you'll see a few key features, notably the Brandenburg Gate. That beautiful column structure, built in the Napoleonic style, evolved from a symbol of Nazi power to Soviet terror. Below, you can see two images below: one surrounded by barbed wire during the 1960s, the other, in present day.

Let's go "behind the Wall", cross into the East, and "interview" some of those who lived there. And in "going behind the Wall", let's firstly examine "the Wall" itself.

Part I: The 'Wall'

Quote:

- [The Berlin Wall] was one of the longest structures ever built to keep people separate from one another. And from it, Berliners developed what came to be known as Berliner Schnauze, a sort of "in-your-face" attitude of coarse humor and sarcasm.

The Wall itself was huge. Built to heights of ten, 12, and 14 feet, it was "capped" with a roundish top so that people couldn't get a good "grip" on it and possibly vault themselves over the Wall.

At least 136 people died at the Berlin Wall between 1961 and 1989. Some were shot or fatally injured while trying to escape. Others took their own lives when they realized their escape had failed. Still others were mistakenly identified as fugitives and shot.

If someone were to "jump the Wall", what waited for them was a 50 sprint on a gravel track, a sort of "no-man's -land" between the borders. Notice the "guard's tower" on the left in the above picture.

Quote:

Outright "escape" through, over, or around the Wall was futile, so many people found other ways to break through. We'll discuss that later.

Quote:

- Fugitives trying to escape in 1989 first had to get over the inner wall that sealed off the border strip on the GDR side. Then they had to climb a signal fence that, when touched, activated an alarm in the watch towers where the border soldiers were stationed. Having passed the patrol road and a strip created to secure tracks, fugitives had to get over the final barrier, the nearly 12-foot high border wall, before reaching the West.

Outright "escape" through, over, or around the Wall was futile, so many people found other ways to break through. We'll discuss that later.

Part II: The 'Stasi"

As mentioned in the introduction, the Stasi were the "secret police" of sorts that kept order in the GDR. So, just think: Berliners have been subject to a police state since 1933...first with the Strumabteilung (SA), the "Brown Shirts", and the Schutzstaffel (SS), the "secret police", and then with the Stasis in the 1950s. This "police state" would last for about 60 years! First, Nazism, and then, militant Communism. Wow...

Quote:

The GDR would become known as "the most perfected surveillance state of all time". There were 97,000 employees and 173,000 informers. That works out to one Stasi operative for every 63 people.

- Like the Third Reich that preceded it, the East German system depended on the active participation of thousands of ordinary citizens who "shopped" their friends, workmates and colleagues to the authorities. Police states depend upon collusion, not simply upon coercion...

The GDR would become known as "the most perfected surveillance state of all time". There were 97,000 employees and 173,000 informers. That works out to one Stasi operative for every 63 people.

But the Stasi weren't crazy! The weren't irrational and they weren't "bloated bureaucrats"! Examine the quote below:

- “This capitalism is, above all, exploitation! It is unfair. It’s brutal. The rich get richer and the masses get steadily poorer. And capitalism makes war! German imperialism in particular! Each industrialist is a criminal at war with the other, each business at war with the next. Capitalism plunders the planet too…we must get rid of this social system! Otherwise the human race will not last the next fifty years!”

If you think about it, yes, capitalism and the "grab, grab, grab", led to World War I. And we know that World War I led to World War II. So, if you're a German, it's easy to understand your disgust with capitalism.

From our "Communism's Appeal" Activity, we know that "communism", from its Latin root, means "shared common duties". And from the quote above, we know that the East German system depended on the active participation of thousands of ordinary citizens. So, how did East Germans "participate"?

Quote:

In East Germany, information ran in a closed circuit between the government and its press outlets.

Access to books was restricted.

Censorship was a constant pressure on writers, and a given for readers, who learned to read between the lines. The only mass medium the government couldn't control was the signal from western television stations,

...but it tried:

Until the early 1970s the Stasi (state police) used to monitor the angle of people’s antennae hanging out of their apartments, punishing them if they were turned to the west.

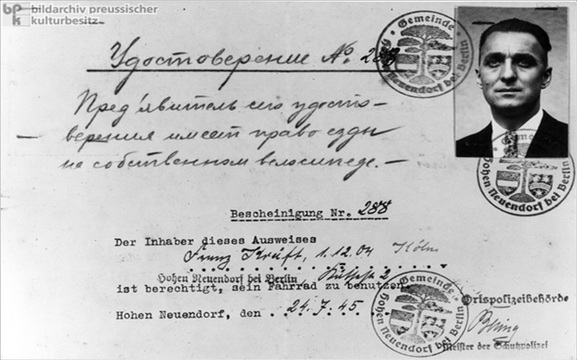

East Berliners were also required to attain a "bicycle pass", much like a driver's license! This July 1945-issued “bicycle pass” ensured that only state-approved “messengers” would be able to ride around East Berlin. (SIDE NOTE: If you know that Queen song, "Bicycle Race", where one of the lyrics reads, "I want to ride my bicycle"...it most likely refers to this!)

The Stasi had used radiation to mark people and objects it wanted to track:

To detect the marked person or object, the Stasi developed personal geiger counters that could be strapped to the body, and would silently vibrate if the officer got a reading.

To this day, you will find that most Stasi members defend their actions. It was a police state. It was communism. It was always close to World War III. They did what was necessary. In regards to the Wall itself, said one former Stasi official: "It was absolutely necessary! It was an historical necessity. It was the most useful construction in all of Germany’s history!"

- It developed a range of radioactive tags including irridated pins it could secretly insert in a person’s clothing, radioactive magnets to place on cars, and radioactive pellets to shoot into tires.

- It developed hand-pump sprays so Stasi operatives could approach a crowed of people and impregnate them with radiation or secretly spray their floor at home so they would leave radioactive footprints everywhere they went.

To detect the marked person or object, the Stasi developed personal geiger counters that could be strapped to the body, and would silently vibrate if the officer got a reading.

To this day, you will find that most Stasi members defend their actions. It was a police state. It was communism. It was always close to World War III. They did what was necessary. In regards to the Wall itself, said one former Stasi official: "It was absolutely necessary! It was an historical necessity. It was the most useful construction in all of Germany’s history!"

Part III: The East Berliners

East Berliners were controlled by the communist Soviet state. It was pure and simple. They grew up learning about Lenin and his greatness. They "pledged allegiance", so to speak, to the Soviet flag, and learned of its greatness in eradicating Nazism. Many of the youth were even members of the "Frei Deutsche Jugend" (FDJ), the "Free German Youth". Their motto: "Seid Bereit”, meaning, “Be Ready”. The above picture seems to resonate quite well with the images of Nazi youth on a few years prior.

Let's examine some of the stories of those who lived behind "the Wall":

The so-called "Tiger Cell" in the Hoheneck Women's Prison.

The so-called "Tiger Cell" in the Hoheneck Women's Prison.

Miriam:

Miriam endured brutal treatment in prison: ‘When I got out of prison, I was basically no longer human’, she would say. In the book, as she reveals her torture in a cold bath, her voice breaks and the author, Anna Funder, wonders if the Stasi beat something out of her that she didn't get back.

Prisoners were referred to by number only, criminal prisoners allowed to abuse political prisoners, a barter system operated for basic needs like tampons, and the confined atmosphere left Miriam’s nerves frayed...so much so that today, she takes all the doors off of rooms in her apartments.

Once released from prison, Miriam is not allowed to study; she cannot get a job and resorts to selling photographs to friends in order to make a meager living. Her husband, Charlie, and Miriam live together but are subject to regular Stasi scrutiny. Charlie works as a writer, mainly for underground publications and had a small book published in West Germany. He would eventually be arrested, subject to torture, and would die in prison. Miriam receives little to no details of her husband's death...

Miriam endured brutal treatment in prison: ‘When I got out of prison, I was basically no longer human’, she would say. In the book, as she reveals her torture in a cold bath, her voice breaks and the author, Anna Funder, wonders if the Stasi beat something out of her that she didn't get back.

Prisoners were referred to by number only, criminal prisoners allowed to abuse political prisoners, a barter system operated for basic needs like tampons, and the confined atmosphere left Miriam’s nerves frayed...so much so that today, she takes all the doors off of rooms in her apartments.

Once released from prison, Miriam is not allowed to study; she cannot get a job and resorts to selling photographs to friends in order to make a meager living. Her husband, Charlie, and Miriam live together but are subject to regular Stasi scrutiny. Charlie works as a writer, mainly for underground publications and had a small book published in West Germany. He would eventually be arrested, subject to torture, and would die in prison. Miriam receives little to no details of her husband's death...

Julia:

The author compares her to a "hermit crab", whisking back into its shell at the slightest sign of contact. She's afraid to talk.

Julia’s goal as an adolescent was to be an interpreter, her fascination with foreign languages leading her to write letters to the outside world in Russian, French and English. She wanted to show that life in the GDR was not so bad, without the drugs, homelessness and prostitution of the West. Academically clever, particularly in languages, Julia is sent, however, to a distant boarding school; a move she feels was a deliberate tactic by the authorities to isolate her. She lived a life not too dissimilar to other East Berliners (black cars that follow her or park outside her home, tapped phone calls, and bags constantly searched) but she struggles with the story of life after the Wall. Eventually, Julia reveals that she was raped soon after the Wall came down. The police were unsympathetic and disinterested, offering her no protection. "So this is orderly chaos", says the author, "the mess that gives rise to all that order".

The author compares her to a "hermit crab", whisking back into its shell at the slightest sign of contact. She's afraid to talk.

Julia’s goal as an adolescent was to be an interpreter, her fascination with foreign languages leading her to write letters to the outside world in Russian, French and English. She wanted to show that life in the GDR was not so bad, without the drugs, homelessness and prostitution of the West. Academically clever, particularly in languages, Julia is sent, however, to a distant boarding school; a move she feels was a deliberate tactic by the authorities to isolate her. She lived a life not too dissimilar to other East Berliners (black cars that follow her or park outside her home, tapped phone calls, and bags constantly searched) but she struggles with the story of life after the Wall. Eventually, Julia reveals that she was raped soon after the Wall came down. The police were unsympathetic and disinterested, offering her no protection. "So this is orderly chaos", says the author, "the mess that gives rise to all that order".

Frau Paul:

The story of Frau Paul is perhaps the most poignant of the book. Her son, Torsten, is born very ill in January 1961. Unable to be properly diagnosed and treated in an Eastern hospital, Torsten is transferred to the Westend Hospital in West Berlin where he is immediately operated on for his life-threatening stomach condition. He survives, but while convalescing, the Wall is erected, sealing him off from his family on the other side. Husband and wife were not allowed to visit the West together in case they failed to return. The emotional demands of not having regular contact with their sick baby took their toll on this woman. They make arrangements to escape, but their plans must be put on hold.

Eventually, the couple start noticing that they are being followed by the Stasi. Frau Paul is snatched off the street and interrogated at Stasi HQ for twenty-two hours. She is offered a deal; help them catch a rogue fugitive and she can see her son. She refuses to snitch on another East Berliner.

Frau Paul takes the author, Anna Funder, to visit the Stasi prison, Hohenschönhausen. They visit the room where she was made to sit for 22 hours on a small wooden stool. The tour also passes small compartments used for iced water torture, completely dark concrete cells and others lined completely with black rubber. In August 1964, Frau Paul and her husband are bought free by 40,000 western marks, but the promise doesn't deliver: Over the course of almost 30 years, 34,000 East Berliners were "bought" by the West. Only nine weren't delivered. Frau Paul was one of those nine. Eventually, she and her son reunite and live life together. They are determined not to talk of the "what if's" of life, but stand as example of those who suffered under Stasi rule.

The story of Frau Paul is perhaps the most poignant of the book. Her son, Torsten, is born very ill in January 1961. Unable to be properly diagnosed and treated in an Eastern hospital, Torsten is transferred to the Westend Hospital in West Berlin where he is immediately operated on for his life-threatening stomach condition. He survives, but while convalescing, the Wall is erected, sealing him off from his family on the other side. Husband and wife were not allowed to visit the West together in case they failed to return. The emotional demands of not having regular contact with their sick baby took their toll on this woman. They make arrangements to escape, but their plans must be put on hold.

Eventually, the couple start noticing that they are being followed by the Stasi. Frau Paul is snatched off the street and interrogated at Stasi HQ for twenty-two hours. She is offered a deal; help them catch a rogue fugitive and she can see her son. She refuses to snitch on another East Berliner.

Frau Paul takes the author, Anna Funder, to visit the Stasi prison, Hohenschönhausen. They visit the room where she was made to sit for 22 hours on a small wooden stool. The tour also passes small compartments used for iced water torture, completely dark concrete cells and others lined completely with black rubber. In August 1964, Frau Paul and her husband are bought free by 40,000 western marks, but the promise doesn't deliver: Over the course of almost 30 years, 34,000 East Berliners were "bought" by the West. Only nine weren't delivered. Frau Paul was one of those nine. Eventually, she and her son reunite and live life together. They are determined not to talk of the "what if's" of life, but stand as example of those who suffered under Stasi rule.

CONCLUSIONS:

- What's one thing you now know about the Berlin Wall itself?

- What are some "WOW!" moments associated with your understanding of the Stasi?

- Summarize the "life stories" of Miriam, Julia, and Frau Paul, and describe what life was like "behind the Wall".