- 1848 -

National Powder Kegs Explode in the Nations of France, Austria, and Prussia

Partner #1: You will be reading first! Below, you'll find various "chapters", so to speak, of the revolutions. You'll be reading the first "chapter", as your partner examines the accompanying image. Then, your partner will show you the image about which you just read, and then you'll switch roles: the reader becomes the "examiner"; the "examiner", the reader.

Chapter 1: Pre-Revolutionary

Sentiment in Austria

It is believed that Emperor Charles VI (1711 – 1740) of the Austrian Habsburg line once declared that he would rather be a hewer of wood than rule like a British monarch. And it is with this statement, one of a pure admonishment of the English model of democracy, that Austria, Prussia, France and the Revolutions of 1848 begin their story.

Outside of the principality of Hungary and the Venetian duchy newly acquired by the Austrians in a treaty with Napoléon, there were no representative institutions worthy of the name in the Austrian Habsburg Empire. Since 1835 the Emperor had been the mentally disabled Ferdinand I who was infamous for an outburst in which he yelled at his courtiers, ‘I am the Emperor and I want dumplings!’ Furthermore, the financial cost of maintaining Austrian power in Europe was at a great intensity: between 1815 and 1848, the army swallowed some 40 per cent of the government budget, and paying interest alone on the state debt digested a further 30 per cent. One of the great weaknesses of Metternich’s ‘system’ that was exposed in 1848 was that it had scant money left in its coffers to cope with the worst economic downturn of the nineteenth century and so could do little to soothe the people’s distress.

Outside of the principality of Hungary and the Venetian duchy newly acquired by the Austrians in a treaty with Napoléon, there were no representative institutions worthy of the name in the Austrian Habsburg Empire. Since 1835 the Emperor had been the mentally disabled Ferdinand I who was infamous for an outburst in which he yelled at his courtiers, ‘I am the Emperor and I want dumplings!’ Furthermore, the financial cost of maintaining Austrian power in Europe was at a great intensity: between 1815 and 1848, the army swallowed some 40 per cent of the government budget, and paying interest alone on the state debt digested a further 30 per cent. One of the great weaknesses of Metternich’s ‘system’ that was exposed in 1848 was that it had scant money left in its coffers to cope with the worst economic downturn of the nineteenth century and so could do little to soothe the people’s distress.

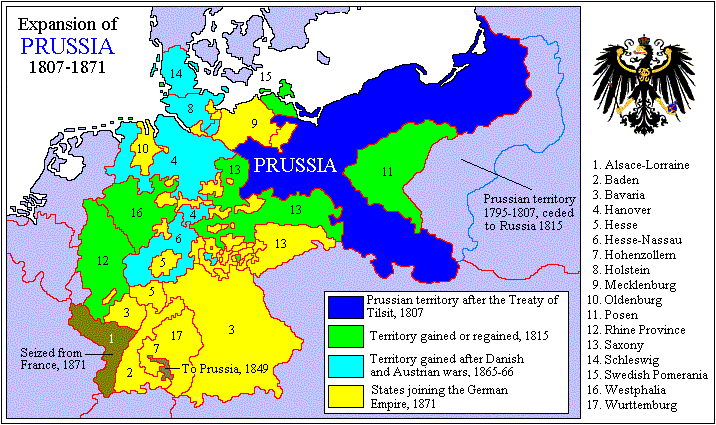

Chapter 2: Pre-Revolutionary

Sentiment in Prussia

Chapter 3: Pre-Revolutionary

Sentiment in France

To the west, still reeling from the effects of Napoléonic dominance, French leader Louis-Philippe initially held fast to his liberal convictions forged in fire by the Revolution of 1830. When he arrived in Paris, he symbolically embraced the aged Marquis de Lafayette, hero of both the American and French Revolutions, on a balcony at the Hôtel de Ville, the seat of the capital’s municipal government. With Louis-Philippe, the French ruling administration, dubbing themselves the July Monarchy, promised to reconnect with France’s revolutionary heritage by restoring the tricolour: never again would the Bourbon white banner flutter as the national flag. Under its new leader, France would experience some of the fastest economic growth in its history. In the late 1830s, it expanded and improved the road system. In 1842 the government embarked on the construction of a railway network, laying some nine hundred miles of track, which made new demands on heavy industries like coal, iron, steel and engineering, so that they expanded in turn. For this reason, some economic historians identify the 1840s as the period of ‘take-off’ in French industrialization.

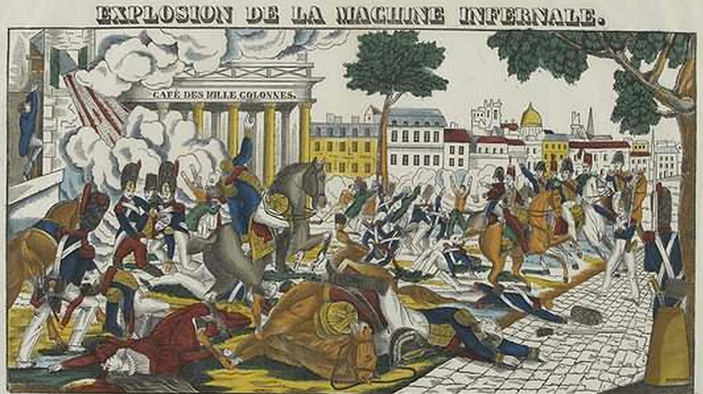

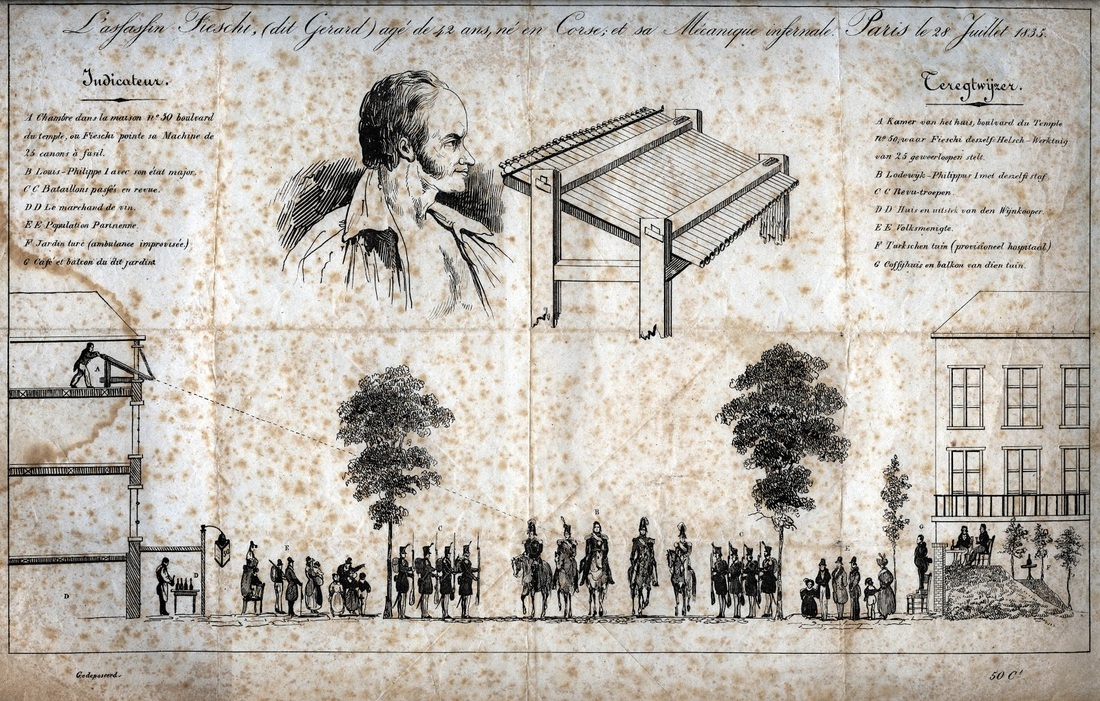

Chapter 4: French Tensions Escalate

Chapter 5: Calming Tensions

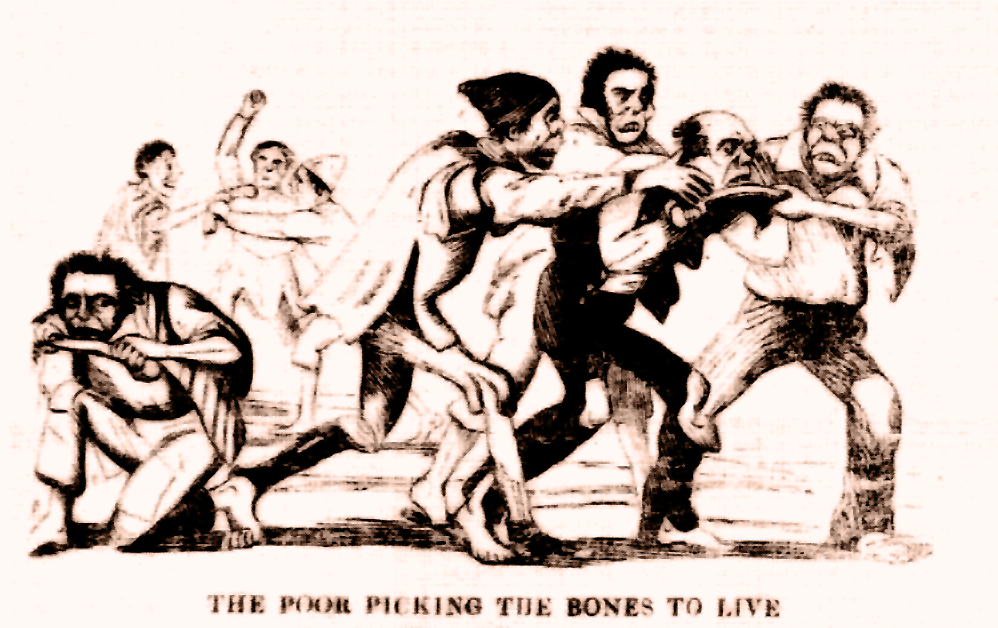

But the revolution would not take its cannibalistic turn just yet. Tempers could calm, arms would be lowered, and cooler heads would prevail. In the late 1830s, no revolution would happen in France, nor would it spread to Austria, Prussia, or Italy. Yet, the prophetic words of French diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville would prove hauntingly accurate. On 29 January 1848, he rose in the Chamber of Deputies and warned his colleagues that sooner or later the grumbling discontent of the French masses would explode in the most fearful of revolutions: ‘I believe that right now we are sleeping on a volcano . . . can you not sense, by a sort of instinctive intuition . . . that the earth is trembling again in Europe? Can you not feel . . . the wind of revolution in the air?’

Chapter 6: Revolutionary Explanations

Chapter 7: A Light Shines on Milan

The first violent confrontation of 1848 arose in Milan, Italy in the form of perhaps the first concerted anti-smoking campaign in modern history. Since Austria’s Italian provinces were among its most lucrative sources of taxation, the Italian revolutionaries, inspired by the example of the Boston Tea Party of 1773, organized a boycott of tobacco, the tax on which gave the Austrian treasury a significant portion of its revenue. On 3 January, a Milanese, offended by an Austrian soldier puffing exaggeratedly at a cigar, knocked it out of his mouth. A scuffle ensued and some citizens were beaten up by soldiers. A larger crowd of civilians then gathered and retaliated by attacking the troops. The garrison came out in strength, putting down the ‘tobacco riot’ by killing six and wounding fifty civilians. An isolated incident of sorts would radiate violently in the French newspapers.

Chapter 8: France Takes Notice

Chapter 9: Germans Unite!

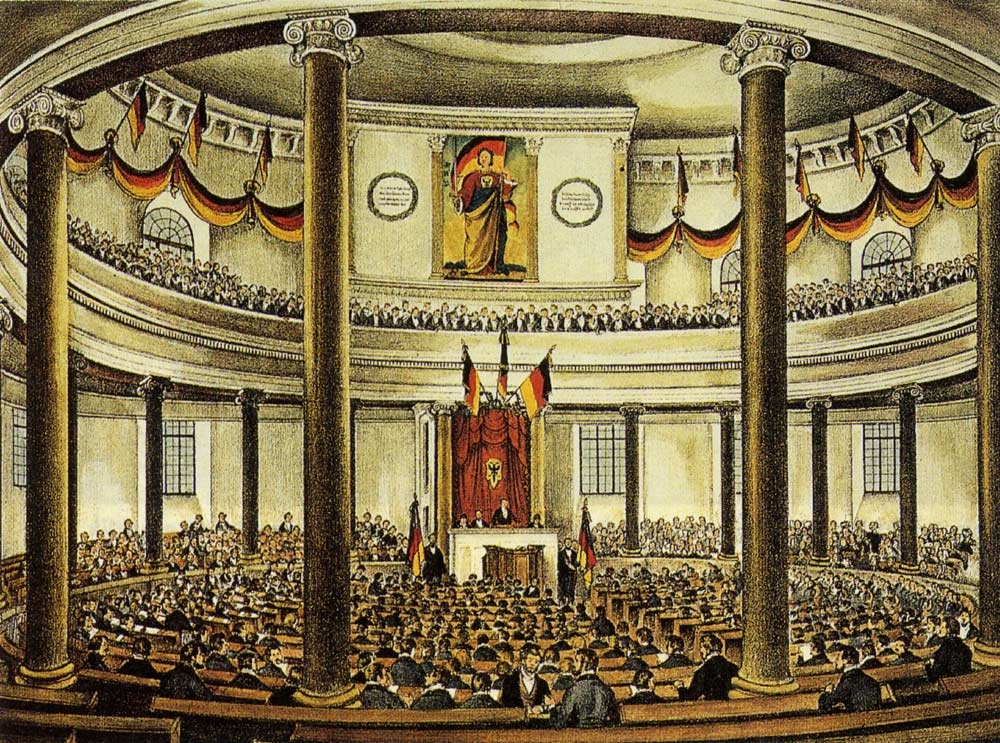

Word of the February days in Paris spread like a dynamic pulse and electrified Europe, hastened by the wonders of the modern world. The speed with which the wave of revolutions swept across Europe was due to the wonders of modern technology. In 1789 it took weeks for news - carried, at its fastest, on horseback or under sail - for the fall of the Bastille to be relayed across Central and Eastern Europe. In 1848, thanks to steamships and a nascent telegraph system, reports were being heard within days or even minutes. On hearing word of the February revolution in Paris, Tsar Nicholas I is alleged to have burst into a palace ballroom, proclaiming, ‘Saddle your horses gentlemen! A Republic has been declared in France.’ The enthusiasm among German liberals and radicals was infectious. In Mannheim, Germany, the republican lawyer Gustav Struve organized a political rally, drafting a petition demanding freedom of the press, trial by jury, a popular militia with elected officers, constitutions for every German state and the election of an all-German parliament. While individual states were being reformed, liberals and radicals sensed the opportunity to recast all of Germany into a new, more unified shape.

Chapter 10: On to Austria

Chapter 11: The People's Demands

Throughout the Austrian Habsburg Empire, authority appeared to be collapsing in every corner of their realm - in Budapest, Prague, Milan and Venice. Concessions were made out of the grim necessity for survival. The so-called ‘Twelve Points’ became Hungary’s revolutionary program. They included the standard demands of 1848

- free speech,

- ‘responsible government’ (meaning a ministry answerable to parliament),

- regular parliaments,

- civil equality and religious freedom,

- a national guard,

- equality of taxation and

- trial by jury.

Chapter 12: The Battle of Berlin

Chapter 13: A Harrowing Conclusion?

The social unity found in Prussia, Austria, and even France would not last, however The revolutions of 1848 were to some extent built on what French historian Georges Duveau has called a ‘lyrical illusion’. This ‘illusion’ rested, first, on the idea that the people had indeed triumphed over the old regime and even defeated its armed forces. In most European states affected by the revolutions the structures of the old order were battered and severely damaged but not entirely leveled - except in France, the only country where the revolution destroyed the monarchy. Everywhere else, the monarchy remained - and with it ministers and advisers who were determined to resist further change or to undo the revolution altogether…