- 1848 -

National Powder Kegs Explode in the Nations of France, Austria, and Prussia

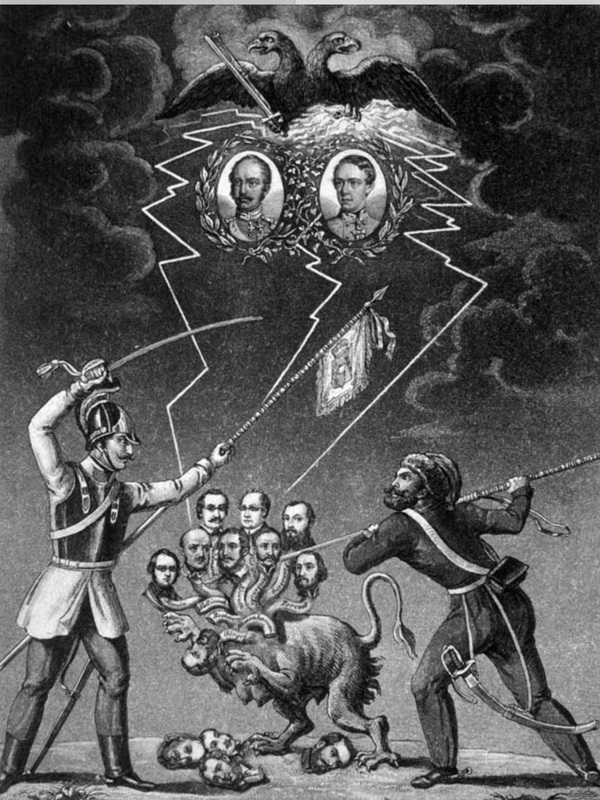

Partner #2: You will be "examining" first! Below, you'll find various "chapters", so to speak, of the revolutions. You'll be examining an image from the first "chapter", as your partner reads about the accompanying image. Then, your partner will show you the image about which they just read, and then you'll switch roles: the reader becomes the "examiner"; the "examiner", the reader.

Chapter 1: Pre-Revolutionary

Sentiment in Austria

It is believed that Emperor Charles VI (1711 – 1740) of the Austrian Habsburg line once declared that he would rather be a hewer of wood than rule like a British monarch. |

Since 1835 the Emperor of Austria had been the mentally disabled Ferdinand I who was infamous for an outburst in which he yelled at his courtiers, ‘I am the Emperor and I want dumplings!’ |

Chapter 2: Pre-Revolutionary

Sentiment in Prussia

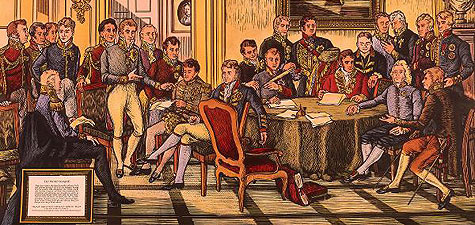

North of Austria, the teenaged Prussian Empire was booming. The Rhineland territory, with its advanced economy and relatively positive experience of Napoleonic rule, had been given to Prussia in 1815, to strengthen Germany against France. This made Prussia a kingdom of two halves - the east dominated by the landed nobility, with their great estates and their peasants, who until 1807 had been enserfed, and the west, with its strong manufacturing base and burgeoning middle class. Furthermore, Prussia was a cultural force with which to reckon: In Prussia, where there was a well-established tradition of state schooling, an impressive 80 per cent of people were literate.

Yet, on the Prussian throne sat Frederick William IV, descendent of Frederick William the “Great Elector”. But this Frederick William proved to be a different sort of ruler as he once explained to a disappointed liberal official that ‘I feel I am king solely by the grace of God.’ A constitution would, he said, make the whole idea of monarchy ‘an abstract concept, by dint of a piece of paper.

Yet, on the Prussian throne sat Frederick William IV, descendent of Frederick William the “Great Elector”. But this Frederick William proved to be a different sort of ruler as he once explained to a disappointed liberal official that ‘I feel I am king solely by the grace of God.’ A constitution would, he said, make the whole idea of monarchy ‘an abstract concept, by dint of a piece of paper.

Chapter 3: Pre-Revolutionary

Sentiment in France

Chapter 4: French Tensions Escalate

But as the calendar years progressed from 1830 to 1831, 1832, 1833, and 1834, revolutionary unity dissolved, replaced by revolutionary fervor. The Parisian insurrection of April 1834 - the inspiration for the uprising in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables - ended with a massacre on the rue Transnonain, when enraged soldiers clearing revolutionary snipers from a tenement room by room indiscriminately slaughtered twelve civilians whom they found sheltering there. The killing of innocents left an indelible stain on the July Monarchy. French revolutionary republicans reacted with more violence, including, in 1835, a truly horrific assassination attempt on the King by a twenty-five-barrelled gun, dubbed an ‘infernal machine’, in which some fourteen people were killed - but not Louis-Philippe, who escaped with a single bruise.

Louis-Philippe’s hand was forced, and he had to act quickly. The September Laws of 1835 imposed press restrictions: newspapers could be prosecuted for proposing another system of government or for insulting the King - although that did not stop the bold caricaturist Honoré Daumier (who was prosecuted for his cartoons) from transforming Louis-Philippe’s jowly features into a pear shape, an image which stuck.

Louis-Philippe’s hand was forced, and he had to act quickly. The September Laws of 1835 imposed press restrictions: newspapers could be prosecuted for proposing another system of government or for insulting the King - although that did not stop the bold caricaturist Honoré Daumier (who was prosecuted for his cartoons) from transforming Louis-Philippe’s jowly features into a pear shape, an image which stuck.

Chapter 5: Calming Tensions

Chapter 6: Revolutionary Explanations

Why 1848? Why not closer to the advent of the French Revolution? And more directly, why revolt during a time of unprecedented peace throughout the continent of Europe? The reasons are three-fold:

- POPULATION: As one French satirist put it, there must have been a population explosion because ‘there were twenty times more lawyers than suits to be lost, more painters than portraits to be taken, more soldiers than victories to gain, and more doctors than patients to kill’. Quite frankly, the post-Napoleonic population surge resulted in an exacerbation of population struggles. In social terms the collapse of the conservative orders of Metternich and the like in 1848 was a crisis of ‘modernization’ in the sense that the European economy and society were changing, but they had not yet been adequately transformed to absorb the intense pressures of population growth and, above all, to address the desperation of artisans, craft workers and peasants.

- ECONOMICS: A cyclical trade slump combined with harvest failures ensured that the bleak era would be remembered as the ‘hungry forties’. The crisis began in earnest in 1845, but then continued unabated until almost the end of the decade. The great tragedy was that, while the grain harvests failed, so too did the potato, which was the main back-up crop. It was afflicted by a fungus, popularly called the ‘blight’, which turned the tubers into a rotten mush.

- CLASS DIVISIONS: Since 1840 the French political landscape had been dominated by the figure of Prime Minister François Guizot. A historian, he was Protestant, bourgeois, eloquent, bright and rather arrogant: when pressed with demands to extend the right to vote, he famously replied, ‘Enrichissez-vous’ - ‘Get rich’ - in order to qualify for the suffrage.

Chapter 7: A Light Shines on Milan

Chapter 8: France Takes Notice

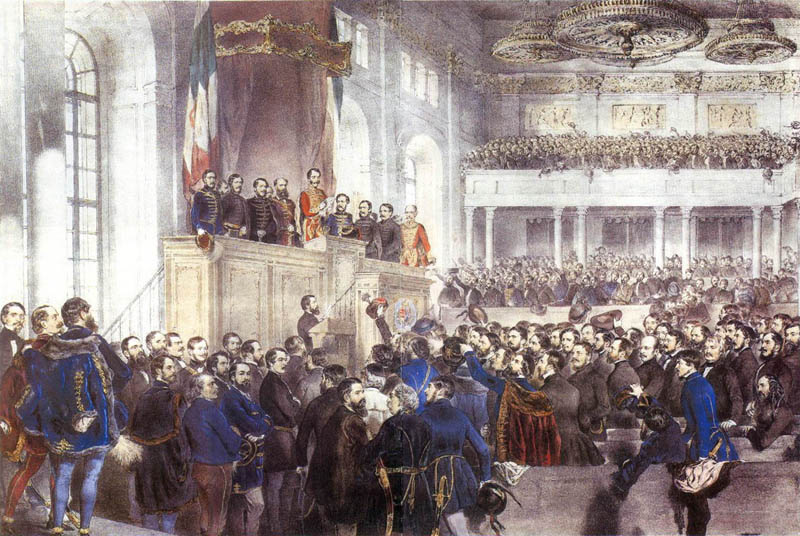

News of the slaughter pulsated around the city: for Parisians, the massacre seemed to signal the onset of a government effort to reassert its authority by crushing force. The Parisians did what they do best: took to the streets. While the Château d’Eau rail station burned, the Louis-Phillippe collapsed in a chair in his study, watched by his hapless courtiers. Politicians offered him conflicting advice, but it was the slippery newspaperman Émile Girardin, editor of La Presse, who at midday strode forward and brusquely urged Louis-Philippe: ‘Abdicate, Sire!’

Instead, Louis-Phillippe restored to desertion: he dressed (as he liked to do) in plain, bourgeois clothes, walked briskly with his wife Marie-Amélie through the Tuileries Gardens and boarded a carriage waiting on the Place de la Concorde, from where, escorted by loyal cavalrymen, they drove off, reaching the northern French coast on 26 February. There, the British vice-consul (showing either a profound lack of imagination or a wry sense of humor) gave the royal couple the alias of ‘Mr. and Mrs. Smith’. On 3 March they landed in Britain, where Louis-Philippe would die in August 1850. In the early hours of 25 February, French writer Alphonse de Lamartine dramatically strode out on to a balcony, declaring: ‘The Republic has been proclaimed!’ His words unleashed a roar of ecstatic cheering. The Second Republic of France was thusly established.

Instead, Louis-Phillippe restored to desertion: he dressed (as he liked to do) in plain, bourgeois clothes, walked briskly with his wife Marie-Amélie through the Tuileries Gardens and boarded a carriage waiting on the Place de la Concorde, from where, escorted by loyal cavalrymen, they drove off, reaching the northern French coast on 26 February. There, the British vice-consul (showing either a profound lack of imagination or a wry sense of humor) gave the royal couple the alias of ‘Mr. and Mrs. Smith’. On 3 March they landed in Britain, where Louis-Philippe would die in August 1850. In the early hours of 25 February, French writer Alphonse de Lamartine dramatically strode out on to a balcony, declaring: ‘The Republic has been proclaimed!’ His words unleashed a roar of ecstatic cheering. The Second Republic of France was thusly established.

Chapter 9: Germans Unite!

Chapter 10: On to Austria

In Austria, One Viennese wrote excitedly that ‘The word “constitution” is giving a new movement to the waves of the time - a movement that will be felt over the whole globe and which will strike many a pillar of absolutism with thunder and lightning.’ Those parts of Central Europe that so far had merely effervesced at the news from Paris now boiled over on the word from Vienna. By April, 1848, Emperor Charles VI had agonizingly been pressed into resigning. Metternich slipped out the Hofburg government building minutes before the deadline for a new constitution. expired. He and his wife Melanie left Vienna that night in a discreet fiacre boarded another carriage outside the city and drove to a train, which spirited them across Europe. They spent almost a fortnight in The Hague, a city in the Netherlands, waiting asylum in England. He never received this permission.

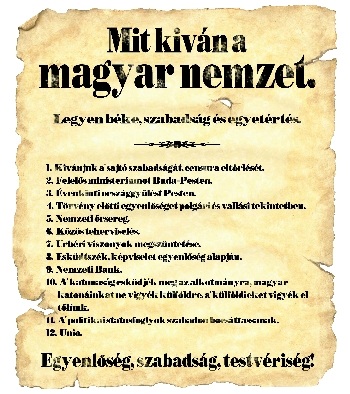

Chapter 11: The People's Demands

Chapter 12: The Battle of Berlin

Northward in Germany, action of committees was not so pleasant. In the Prussian city of Berlin, one promise had not been made: to pull the troops out of the city. The battle for Berlin was one of the most ferocious anywhere in Europe in 1848. When the troops attacked the barricades, they used artillery and then marched head-on against the fortifications. Faced with the ferocity of the insurgents, the frustrated, furious and often frightened soldiers fired indiscriminately into houses, through doors and windows. Houses burst into flames and burned through the night. In all some nine hundred people were killed in an afternoon and night of fighting - eight hundred of them on the insurgents’ side.

Finally, on March 21, 1848, swept along by the popular tide, Frederick William issued a proclamation, in which he declared: ‘I have today taken the old German colors and have put Myself and My people under the venerable banner of the German Reich. Prussia henceforth merges into Germany.’ This was deliberately vague, but for now it seemed to satisfy the clamor for Prussian leadership of a united Germany. He would also announce that he would grant a constitution. Yet, playing the role of revolutionary monarch did not suit a king who had been forced to yield most of the concessions. Three days later he and his family abandoned the city for Potsdam and the royal palace of Sans-Souci, protected by elite guard regiments. Safe in his palace, the King began bitterly to feel the humiliation of the March revolution: ‘We crawled on our stomachs.’

Finally, on March 21, 1848, swept along by the popular tide, Frederick William issued a proclamation, in which he declared: ‘I have today taken the old German colors and have put Myself and My people under the venerable banner of the German Reich. Prussia henceforth merges into Germany.’ This was deliberately vague, but for now it seemed to satisfy the clamor for Prussian leadership of a united Germany. He would also announce that he would grant a constitution. Yet, playing the role of revolutionary monarch did not suit a king who had been forced to yield most of the concessions. Three days later he and his family abandoned the city for Potsdam and the royal palace of Sans-Souci, protected by elite guard regiments. Safe in his palace, the King began bitterly to feel the humiliation of the March revolution: ‘We crawled on our stomachs.’