The Revisionist

and Modernist

Point of View

Claim: The English Civil War was NOT Inevitable, but was the result of Short Term Errors committed by

King Charles I and Lingering

Scottish and Irish Tensions

The Whigs and Marxists place the blame on James I and the economic problems of the empire. But…is it all James fault? Modernists say no. In fact, historian Christopher Durston (1993) states that,

- “There can be no doubt that James possessed some major shortcomings as a ruler, the most damaging of which (included) his inability to live within his financial means…He was emphatically not, however, the total disaster that is found in the pages of the Whig histories”.

- “James was far from being an ideal king, but he was equally far from being the ‘wisest fool in Christendom’… Elizabeth’s legacy to the new king in 1603 was not a good one…James’ record in dealing with the problems was much better than he was often given credit for”. (Barry Coward, 1994)

- “There are no grounds for calling the first truly British sovereign (monarch) ‘James the Great’, but he deserves to be remembered as ‘James the Just’ or ‘James the Well-intentioned’…James’ subjects were lucky to have him as their king”. (Roger Lockyer, 1998)

|

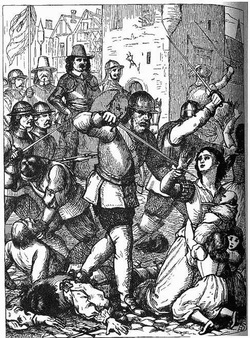

Put simply, according to historian John Hirst, Charles was “ill-fitted” to be king. But Charles’ faults started long before the "civil war year" of 1642. Assuming the throne upon the death of James I in 1625, it seems as if the new king didn’t exactly understand the subtleties of his religious obligations. Ever since the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 in which Catholic "terrorists" attempted to blow up the Houses of Parliament, English Catholics had been in a state of disenfranchisement: forced baptism, forced oaths of loyalty, and in certain cases, seizures of land and assets. Over the next decade, English religious tensions would seize under the following new regulations:

In 1625, as one of his first orders of business, Charles would issue the Act of Revocation, seizing all royal and church lands that were “gifted” by the Crown. In essence, Charles’ administration took back all “land gifts” dating back to 1540. |

In seemingly a “final blow” to the Catholic faith, Charles demanded the issuance of a new “Catholic Prayer Book”, reformed to the standards of the Protestant faith. Scots, now forced to read this new book, were outraged: the book, according to them, contained foundational errors, completely misrepresented the act of communion, and was imposed completely without any Catholic consultation. As Charles did not visit Ireland until 1633, the recently “land-seized” Irish felt completely omitted in this religious overhaul.

By 1637, a full-on Scottish revolt gripped the island nation. Some even feared that the Scots would invade their southern brothers. In April 1640, Charles was forced to “call” Parliament. Remember, James had “dissolved” them in 1611, called them once in 1621, but over the next 19 years, Parliament was essentially nullified. Why was Charles “forced” to call his counsellors? Quite frankly, the rebellions over the Prayer Book, the threat of a Scottish invasion, and the continued problems of finance. Eventually, Parliament and the King decided upon the Nineteen Propositions which decreed the following:

By 1637, a full-on Scottish revolt gripped the island nation. Some even feared that the Scots would invade their southern brothers. In April 1640, Charles was forced to “call” Parliament. Remember, James had “dissolved” them in 1611, called them once in 1621, but over the next 19 years, Parliament was essentially nullified. Why was Charles “forced” to call his counsellors? Quite frankly, the rebellions over the Prayer Book, the threat of a Scottish invasion, and the continued problems of finance. Eventually, Parliament and the King decided upon the Nineteen Propositions which decreed the following:

- The King gives up prerogative powers over army

- Parliament could choose the king’s ministers

- Parliament controlled church

- Parliament could appoint guardians for the royal children

But, as historians would note, the “billiard ball” effects of the Scottish threat and the new Irish Rebellion in October 1641 would pour “gas on the fire” of the lingering problems of financial woes. For centuries, kings could use a “back door” tax known as “shipping money” to collect revenue. In essence, if the king ever felt that a naval invasion was imminent, he could demand that coastal towns pay a tax so that the king could purchase new ships. In 1635, Charles would issue the following warning:

- Spain and France are joining together to root out our religion... They have a large number of soldiers in Brittany ready to invade us... The great business of providing money for ships, which used to be charged on the port towns and neighbouring shires, is too heavy for them alone, therefore the Council have cast up the whole charge of the fleet, and have divided it among all the counties.

- I cannot devise any way to get it (Ship Money) until corn harvest... Most of it is unpaid... whether poverty... a disease which hath been too long in this county... or the new charges for maintenance of soldiers, or the news of the Parliament's dissolution or other causes... I know not.

Charles would back off his demand for “ship money” by the end of 1641, but it wouldn’t prevent looming tensions from exploding the next year. The combination of an “ill-fitting king”, financial problems, and dual rebellious threats of Ireland and Scotland would result in the English Civil War, 1642 to 1649.