FOREIGN POLICY THROUGH THE EYES OF

...WAR AND CONFLICT

Up to this point, we've seen the future of the American foreign policy through economic connectivity and diplomatic relationships. But, we must examine the inevitable: war and conflict.

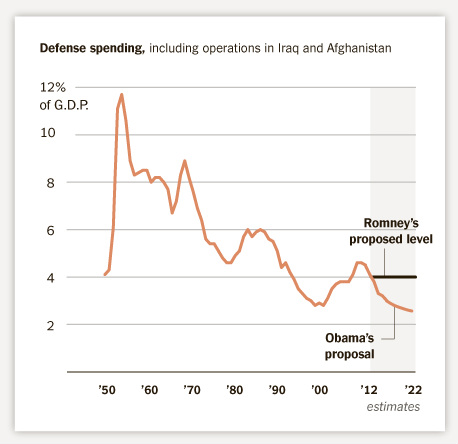

Over time, the United States has spent LESS on defense spending as a percentage of our yearly economy. And yes, Mitt Romney would've liked to spend slightly more than Obama, but the truth is, our military budget is going down. So, what does the future look like? Let's examine weaponry first.

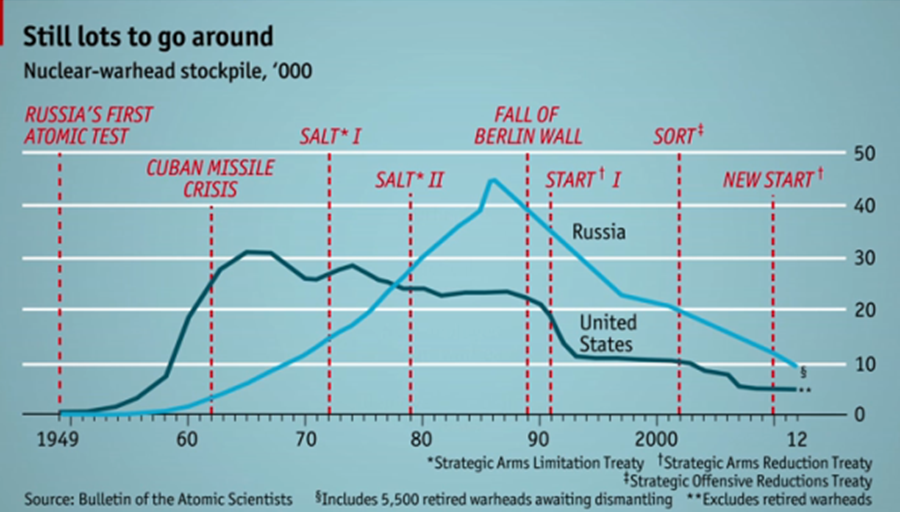

The greatest weapon ever to shake the earth was the nuclear weapon. Yet the United States is on a continued downgrade of stockpile. The Atlantic Monthly magazine states the following:

1. Do you agree? Is the "decrease in spending on nuclear weaponry" something we should be doing? Why?

2. Trace the evolution of nuclear warfare throughout history, using the above provided graph. Simply create a "story" that describes the graph. You can start with the following prompt: "In the beginning, the United States was winning the 'nuclear game'. Then, in 1958..."

The Atlantic also says that,

And with this, we must now discuss drones and drone warfare as the future of American war and conflict.

- One of [Obama's] least discussed [foreign policy plans] is a decrease in spending on nuclear weaponry. It's not clear how much, and it's almost certainly a tiny fraction of what we could cut (the U.S. could still easily annihilate the globe several times over), but even a symbolic cut would be an important step toward Ronald Reagan's dream of eradicating all nuclear weaponry. We'll probably need to maintain some for deterrence purposes as long as China possesses warheads and Iran and North Korea pursue them, but there's no reason we need 5,113 warheads to deter one from Pyongyang. Extra warheads is an invitation to further proliferation from competitors and increases the likelihood of theft or an accident.

1. Do you agree? Is the "decrease in spending on nuclear weaponry" something we should be doing? Why?

2. Trace the evolution of nuclear warfare throughout history, using the above provided graph. Simply create a "story" that describes the graph. You can start with the following prompt: "In the beginning, the United States was winning the 'nuclear game'. Then, in 1958..."

The Atlantic also says that,

- When Obama picked CIA director [Chuck Hagel] as his new Secretary of Defense, he was making a statement about how he wanted the Pentagon [the building in Washington, D.C. that controls our U.S. military] to evolve. The U.S. military has increasingly emphasized a CIA-tinged strategy of drones, special forces, cyber attacks, and secret operations against threats from terrorists to Iranian nuclear scientists. It's a strategy meant to deter and manage threats, not eradicate them outright, and to be cost-effective. Wired's Spencer Ackerman exaplains that, under our new Pentagon, the "Shadow War" will be continuing, with military-led global surveillance programs actually increasing.

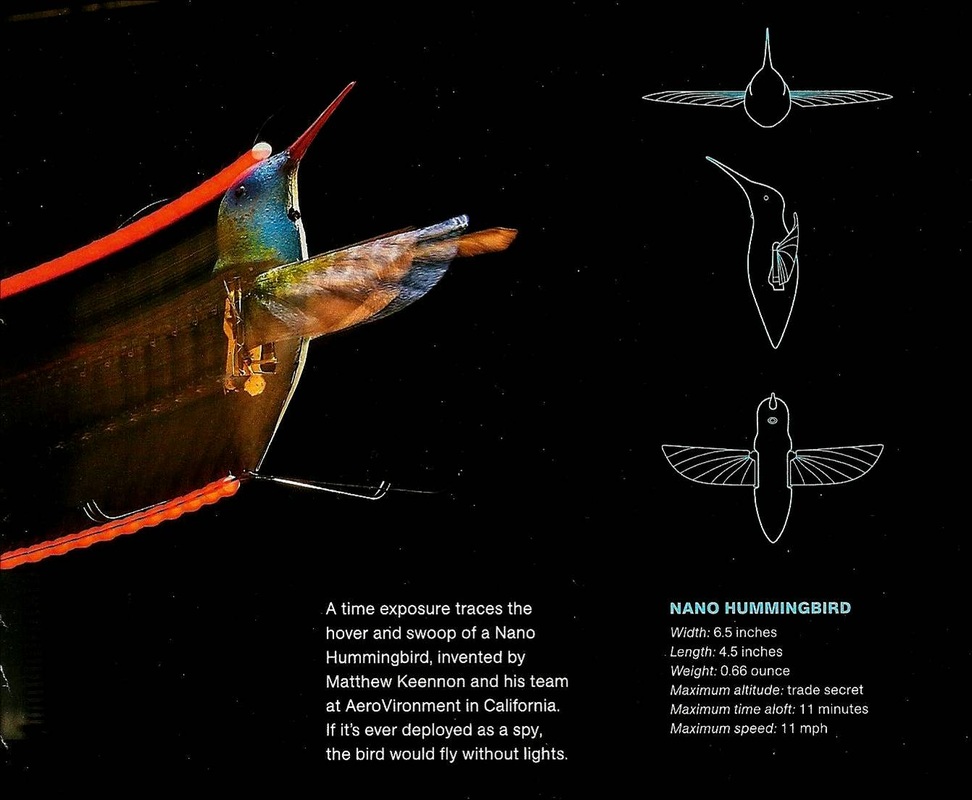

And with this, we must now discuss drones and drone warfare as the future of American war and conflict.

A "drone" is a male honey bee that does the work of the queen bee. It doesn't really think much, doesn't really ever rest, and is constantly working for the betterment of the colony.

Similarly, military drones do the same thing: don't think, don't rest, and always work! They're unmanned aircraft, meaning no human pilot is inside of them. In February 2013,TIME Magazine published an entire issue on this very topic: "Rise of the Drones". And in their main article, Drone Home, they discuss the merits and strengths, disadvantages and myths about drones and their usage. Read excerpts from the article below and answer the questions.

Similarly, military drones do the same thing: don't think, don't rest, and always work! They're unmanned aircraft, meaning no human pilot is inside of them. In February 2013,TIME Magazine published an entire issue on this very topic: "Rise of the Drones". And in their main article, Drone Home, they discuss the merits and strengths, disadvantages and myths about drones and their usage. Read excerpts from the article below and answer the questions.

A few months ago I borrowed a drone from a company called Parrot. Officially the drone is called an A.R. Drone 2.0, but for simplicity’s sake, we’re just going to call it the Parrot. The Parrot went on sale last May and retails for about $300.

A drone isn’t just a tool; when you use it you see an act through it-you inhabit it. [Put simply] drones extend our physical presence. They are, along with smart phones and 3-D printing, one of a handful of genuinely transformative technologies to emerge in the past 10 years.

They’ve certainty transformed the U.S. military: of late, the American government has gotten very good at extending its physical presence for the purpose of killing people. Ten years ago the Pentagon had about 50 drones in its fleet; currently it has some 7,500. More than a third of the aircraft in the Air Force’s fleet are now unmanned. The U.S. military reported carrying out 447 drone attacks in Afghanistan in the first 11 months of 2012, up from 294 in all of 2011. Since president Obama took office, the U.S. has executed more than 300 covert drone attacks in Pakistan, a country with which we’re not at war. Already this year there are credible reports of five covert attacks in Pakistan and as many eight in Yemen, including on January 21, the day of Obama’s second inauguration. The Pentagon is planning to establish a drone base in northwestern Africa.

The military logic couldn’t be clearer. Unlike, say, cruise missiles, which have to be laboriously targeted and prepped and launched over a period of hours, drones are a persistent presence over the battle field, gathering their own intelligence and then providing an instantaneous response. They represent a revolution in the idea of what combat is: with drones the U.S. can exert force not only instantly but undeterred by the risk of incurring American causalities or massive logistical bills, and without the terrestrial baggage of geography; the only relevant geography is that of the global communications grid. In the words Peter Singer, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the author of Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century, drones change “everything from tactics to doctrine to overall strategy to how leaders, the media and the public all conceptualize and decide upon this thing we call war.”

Strictly by thenumbers, America’s drone campaign has been an overwhelming success. According to the New America Foundation, a nonprofit public-policy institute bases in Washington, U.S. drone attacks have claimed the lived of more than 50 high-value al-Qaeda and Taliban leaders. But the seductive theoretical simplicity of drone warfare- omniscient surveillance, surgical precision, zero risk- has led the nation into a labyrinth of confusion and moral compromise. In 2012 Obama described the governments drone campaign as “a targeted, focused effort at people who are on a list of active terrorists trying to go in and harm Americans” that hasn’t caused “a huge number of civilian causalities.”Whether this is accurate may depend on what the word huge means to you. It’s hard to get good statistics, [as drone strikes are secretive and carried out by various agencies] but the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a U.K. nonprofit, estimates that since 2004, CIA drone attacks have killed 2,629 to 3, 279, of whom 261 to 305 were civilians.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has been using Predators to monitor the Mexican border since 2005. It currently fields a fleet of 10 and has put in 14 more. Americans are great and heedless adopters of new technologies and new technologies are as seductive, promise so much at so little political and financial and human cost, as drones. They give us tremendous new powers, and they seem to ask very little of us in return. Obama captured the singular quality of drone warfare precisely in a remark that appears in Mark Bowden’s recent book The Finish. “There’s a remoteness to it.” He said, “that makes it tempting to think that somehow we can, without any mess on our hands, solve [difficult] security problems.” That illusion is just what makes drones such a challenge, especially as we introduce them into our own country. Drones don’t just give us power, they tempt us to use it.

A drone isn’t just a tool; when you use it you see an act through it-you inhabit it. [Put simply] drones extend our physical presence. They are, along with smart phones and 3-D printing, one of a handful of genuinely transformative technologies to emerge in the past 10 years.

They’ve certainty transformed the U.S. military: of late, the American government has gotten very good at extending its physical presence for the purpose of killing people. Ten years ago the Pentagon had about 50 drones in its fleet; currently it has some 7,500. More than a third of the aircraft in the Air Force’s fleet are now unmanned. The U.S. military reported carrying out 447 drone attacks in Afghanistan in the first 11 months of 2012, up from 294 in all of 2011. Since president Obama took office, the U.S. has executed more than 300 covert drone attacks in Pakistan, a country with which we’re not at war. Already this year there are credible reports of five covert attacks in Pakistan and as many eight in Yemen, including on January 21, the day of Obama’s second inauguration. The Pentagon is planning to establish a drone base in northwestern Africa.

The military logic couldn’t be clearer. Unlike, say, cruise missiles, which have to be laboriously targeted and prepped and launched over a period of hours, drones are a persistent presence over the battle field, gathering their own intelligence and then providing an instantaneous response. They represent a revolution in the idea of what combat is: with drones the U.S. can exert force not only instantly but undeterred by the risk of incurring American causalities or massive logistical bills, and without the terrestrial baggage of geography; the only relevant geography is that of the global communications grid. In the words Peter Singer, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the author of Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century, drones change “everything from tactics to doctrine to overall strategy to how leaders, the media and the public all conceptualize and decide upon this thing we call war.”

Strictly by thenumbers, America’s drone campaign has been an overwhelming success. According to the New America Foundation, a nonprofit public-policy institute bases in Washington, U.S. drone attacks have claimed the lived of more than 50 high-value al-Qaeda and Taliban leaders. But the seductive theoretical simplicity of drone warfare- omniscient surveillance, surgical precision, zero risk- has led the nation into a labyrinth of confusion and moral compromise. In 2012 Obama described the governments drone campaign as “a targeted, focused effort at people who are on a list of active terrorists trying to go in and harm Americans” that hasn’t caused “a huge number of civilian causalities.”Whether this is accurate may depend on what the word huge means to you. It’s hard to get good statistics, [as drone strikes are secretive and carried out by various agencies] but the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a U.K. nonprofit, estimates that since 2004, CIA drone attacks have killed 2,629 to 3, 279, of whom 261 to 305 were civilians.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has been using Predators to monitor the Mexican border since 2005. It currently fields a fleet of 10 and has put in 14 more. Americans are great and heedless adopters of new technologies and new technologies are as seductive, promise so much at so little political and financial and human cost, as drones. They give us tremendous new powers, and they seem to ask very little of us in return. Obama captured the singular quality of drone warfare precisely in a remark that appears in Mark Bowden’s recent book The Finish. “There’s a remoteness to it.” He said, “that makes it tempting to think that somehow we can, without any mess on our hands, solve [difficult] security problems.” That illusion is just what makes drones such a challenge, especially as we introduce them into our own country. Drones don’t just give us power, they tempt us to use it.

3. Why is drone usage "tempting"? What are some of the "dangers" of its use?

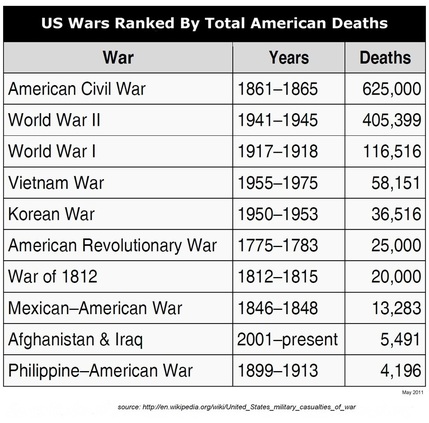

4. PREDICTION: Drone usage during wartime has the capacity to change “...everything from tactics to doctrine to overall strategy." Examine the chart below:

4. PREDICTION: Drone usage during wartime has the capacity to change “...everything from tactics to doctrine to overall strategy." Examine the chart below:

Yes, the chart is only current as of mid-2011, but note that our current war(s) rank last in terms of war deaths (the Philippine-American War was a part of the larger Spanish-American War...) although they're the longest in our country's history. What conclusion can you make about "modern war"? And how might the usage of drones further help this?

5. The article states that the usage of drones leads "...the nation into a [maze] of confusion and moral compromise." What is the debate of drone usage? And in your opinion, should they continue to be used?

5. The article states that the usage of drones leads "...the nation into a [maze] of confusion and moral compromise." What is the debate of drone usage? And in your opinion, should they continue to be used?