gallery walk:

POISON GAS

Perhaps the most infamous war weapon of the First World War was poison gas. Invented by a German military

unit that included five future Nobel laureates, it was its leader, Fritz Haber who had the idea

to use poison gas during wartime.

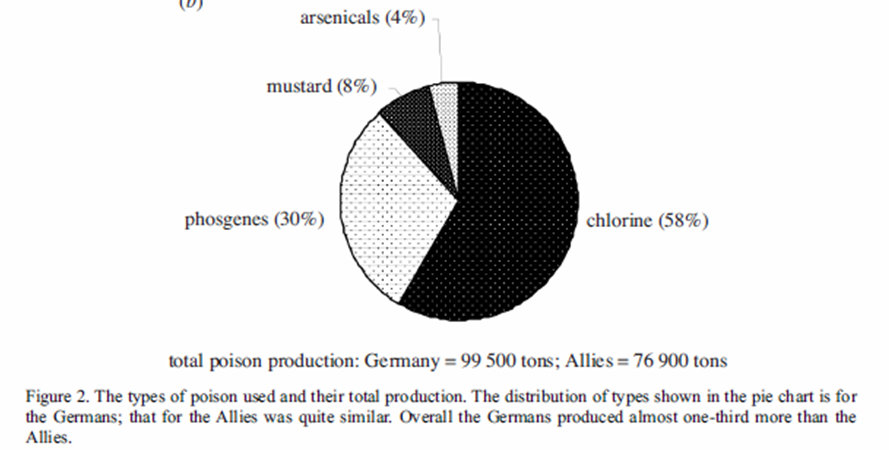

A few distinct types of poison gas were developed for use. The approach was simple: since certain gases are heavier than air, they would naturally "sink" over enemy trenches, assuming that the gases would be carried by "friendly" wind currents. But, in order to be truly effective, the gasses needed to be lethal. This meant large amounts released along a length of front. Phosgene was the deadliest known gas, and previously, some was manufactured, but not in anything like the quantities needed. There was more than enough chlorine. A few deep breaths of air containing containing chlorine at 1000 ppm (parts per million) is fatal.

German production of chlorine gas was about 40 tons per day. Haber left it to the military to determine whether poison gas was legal. The Hague Convention (an internationally-agreed upon set of rules for military operations) banned the use of shells containing poisonous substances, so release from cylinders was, by the letter, legal. Haber was assured that the French were releasing tear gas from exploding rifle bullets and would soon use poisons. Haber was authorized to prepare for a chlorine attack. A total of 1,600 large and 4,130 small cylinders were dug in along 7 kilometers of front. They were assembled in groups of 10 coupled to a manifold leading to a single spout, so that fewer Pioniers (special service operatives) would be needed to open the cocks (shells).

William Van Der Kloot wrote of one particular instance of German gas usage. His words are below:

- Shortly after 1700 hours (5:00 pm), the cocks on the cylinders were opened. Some 150 tons of chlorine gas hissed out of the cylinders. At first it produced a white cloud masking the German line, as the expanding gas cooled the air and formed a mist of water droplets. Then the cloud, heated by the ground temperature, rose to a height of 20–30 meters and turned vivid green-yellow. It rolled inexorably toward the French, pushed by the wind at about a half-meter per second. Where No-Mans-Land (land between opposing forces) was at its narrowest the cloud reached the French trench in 100 seconds; the heavy gas oozed down over the parapet. Men jumped out of the shallow trench, clutching at their throats, and ran for the rear. Many crumpled to the ground. The Allied line was broken. The Canadians on the French right flank knew something was amiss when the late afternoon sun turned green, eyes started to water and men vomited uncontrollably. They identified the cloud as chlorine because it stank just like their drinking water. The German infantry waited for the cloud to disperse. They wore pads of cotton waste soaked in sodium thiosulphate solution, held in place over the nose and mouth with ribbons, the same protection used by workers in chemical factories. They advanced slowly, mistrusting their masks and skirting the green puffs of gas in the hollows. There was no opposition. It took them several hours to occupy the villages of Langemark and Pilkem, just 3–4 kilometers behind the former French line. They had taken 2,000 prisoners and 51 guns. This was as far as they were ordered to go. There were no reserves to leap-frog over them to push on into Ypres, only a little over 3 kilometers further on. Gas was an important factor in the success, which came close to knocking the Italians out of the war. It was another instance of how effective a weapon gas was against ill-equipped and ill-prepared troops.

The German writer Rudolf Binding saw the results when he was ordered to take his men forward to retrieve abandoned guns:

- The effects of the successful gas attack were horrible. I am not pleased with the idea of poisoning men. Of course, the entire world will rage about it first and then imitate us. All the dead lie on their backs, with clenched fists; the whole field is yellow. They say that Ypres (pronounced ee-PRAY) must fall now. One can see it burning—not without a pang for the beautiful city. Langemarck is a heap of rubbish, and all rubbish heaps look alike; there is no sense in describing one. All that remains of the church is the doorway with the date ‘1620’.

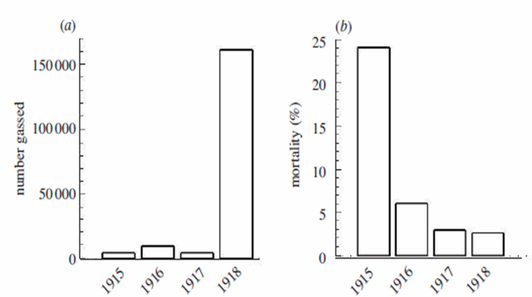

The huge increase in numbers reflects the vast increase in tonnage employed as the war went on. The percentages dying in hospital declined drastically after 1915, because the men had better protective equipment and were trained how to respond. Survival in hospital was much better for those poisoned; overall about 11% of the wounded died in hospital, whereas only about 3% of those gassed died. The question unanswered by these data is whether relatively few died in hospital because so many died immediately on the field. This possibility cannot apply to horse casualties, because their handlers recorded the reason for their death or destruction regardless of where it occurred. From July 1916 to the end of the war the British horses suffered 128,844 gunshot casualties, with a death rate of 44%. In the same period they had 2,431 gas casualties, with a death rate of 9.5%. Again it was better to be gassed than shot.

ANALYSIS QUESTIONS:

- What is "ironic" about the invention (or "inventor") of poison gas?

- How does poison gas "work"? What is its goal?

- In examining the graph and paragraph above, what can you learn about the Allied "response" to gas?